This report continues

and wraps up my visit last week to the Krajina, northwest

Bosnia. I have put a few links at the end of this posting, for

background on Kozarac, Prijedor, and related history.

From Banja Luka I went west to Kozarac, which lies most of the

way to the town of Prijedor. The bus between Banja Luka and

Prijedor passes the exits for the former concentration camp

sites of Omarska and Trnopolje, and goes right by Keraterm.

I slept at the “Kuća mira,” the House of Peace. At the

upper end of Kozarac, this building was formerly the elementary

school. Like nearly every other building and house in Kozarac,

it was torched and bombed during the war, and left as a hulk. I

was present on a dreary April day in 1998 when Emsuda Mujagić,

leader of the women’s organization Srcem do Mira (Through

Heart to Peace) planted a “peace tree” next to the ruins of the

building and declared that it would be rebuilt and a community

center created there. This was before any of the thousands of

displaced Bosniaks had started to return to Kozarac. The

atmosphere was foreboding. I thought Emsuda was fantasizing.

Not long afterwards, someone ripped out the “tree of peace.”

However, return to Kozarac got underway, and today some

thousands of the pre-war residents have returned. The old

elementary school building was beautifully restored, and today

it indeed serves as a center for non-governmental activity and,

occasionally, as a haven for wandering visitors.

Overnight it snowed. I had an early meeting in Prijedor - though

not as early as I thought, since I was unaware of the change to

standard time, which occurs in Bosnia-Herzegovina a week before

it does the United States.

The new look of Kozarac

Sudbin

I met with Sudbin Musić,

secretary of the Udruženje Logoraša

Prijedor ’92 (Association of Concentration Camp Prisoners,

Prijedor 1992). He was a survivor of Trnopolje. On one hand, he

looks like a young 38-year-old. On the other, his pale face gives a

somewhat ghostly, not-so-robust effect that you can only assume is

the result of a traumatic experience from which there is no complete

recovery. But, somehow, Sudbin is energetic, mentally lively, with an

abundant sense of humor and irony. He conveys his feeling of the

tragedy and difficulty of his constituency’s situation, and the

obstacles both within that community and from the outside - through

biting sarcasm - but sometimes also through playfulness.

Sudbin told me about himself: “My father was killed in our village of

Čarakovo at the beginning of the war. I spent two years in Holland

and four in Germany, and then I returned. I came to Sanski Most in

1998. Three days after I returned, they called me into the army. A

week after that, my father’s body was discovered in a well. So there

was no traditional going-away party for me. I spent ten months in

the army.

“There were 700 houses destroyed in Čarakovo; it looked like

Hiroshima. I returned there with my family in 2000. There were two

hundred families that wanted to return, but we were only able to get

donations to repair forty houses. It was like in Rwanda, you could

find human bones everywhere. I found a skull in the garden.

“My first ‘hobby’ was taking care of funeral arrangements, helping

people identify the remains, coordinating with the ICMP

[International Commission for Missing Persons]. My God, what a

hobby. I started to become well known because of my activism. I’m

38; I was 25-26 when I returned.

“The return process ended in 2003. And in that year, people started

to leave. The older people are dying, and the younger ones are

leaving if they can. They get married to someone abroad and then

leave. This is the last phase of the ethnic cleansing.

“In 1991, 2,417 people lived in Čarakovo; the village was 99%

Muslim. From there, 413 people were killed. The rest were taken to

concentration camps, then deported to central Bosnia, and they then

left for Europe and elsewhere.

“In 2003 there were 462 returnees. Now about 350 people live there.

There are 26 children in the elementary school, first through fifth

grade. That is a picture of the success of the ethnic cleansing.”

Sudbin discussed with me the struggle of his organization for the

rights of the concentration camp survivors. He said,

“The question of memory is the most

essential one. There need to be reparations, and we are working on

the status of the survivors. My association is not ethnically-oriented. We are struggling for the rights of all

survivors. That is why we have no money, because we are not

nationalist. There is too much politicization of this issue.”

Spring of 2012 was the twentieth anniversary of the beginning of the

war, the attacks on Prijedor and Kozarac from surrounding Serb

separatist forces, and the formation of the concentration camps.

There has been an upsurge of activism in the municipality - and on

the Internet as well. Survivors and returnees in Prijedor have been

fighting to have the crimes that were committed against them

acknowledged and commemorated, for example, at Omarska. To date

there has been strong resistance against this campaign, especially

from the municipal government headed by Mayor Marko Pavić.

“I’m president of the committee for organization of funerals. More

victims are being exhumed and identified each year. The funerals are

held on July 20th. There are three parts of Prijedor

municipality [that were inhabited by Muslims and that were

targeted]: Kozarac was the first that was destroyed. Then the Old

Town and other Muslim parts of the city. Then the communities on the

left bank of the Sana were destroyed between July 20th

and 26th of 1992. Of all the people killed, 95% were Muslim, including women, children, and old people [The

rest were other non-Serbs, primarily Croats]. No one has been

arrested or prosecuted for these crimes. We are using this day, July

20th, to show the local community and the world that no

one knows about these things.

Mourner at cemetery of wartime victims,

Kozarac

“And we are talking about the 256 women and 102 children who were

killed. We were going to do an exhibit about the women, but this was

forbidden by Pavić. He is the Pharaoh. He is Ramses. He says, ‘You

have to do what I say, and think like I do.’ But we did a

commemoration for the children, and that was a success. We held a

procession through Prijedor, carrying children’s school bags. We

walked starting at noon and finished at 1:00 p.m.

Q: How was this received?

A: “Nothing happened. Then we did something for Human Rights Day on

December 10, and again it was received with indifference. But the

municipal assembly called a special session, exclusively to talk

about our use of the word ‘genocide.’”

I asked if the struggle for commemoration at Omarska would continue.

Sudbin said, “Yes, but how? There is no money. We got a letter from

Pavić that there would be no money from the municipality for this

kind of work, and there is no support from the UNDP either. We are

fighting the fight of Don Quixote.”

Sudbin discussed the position of various return communities and the

capital city: “The return communities are like reservations. These

are local microcosms with micro-economies. Kozarac is Dubai. It is

the golden goose, based on good agricultural land, tourism, and

agriculture, some industry.

“And there is a very large microcosm in Sarajevo, which is the Hong

Kong of Bosnia. It sucks money from the rest of the country. People

there don’t understand that there is also Bosnia on the other side

of Trebević [a mountain to the southeast of Sarajevo].

“Politics in this country is based on the economics of

privatization. In five years we won’t have our own politics, but

that of Zarubezhnjeft [Russian oil company], Mittal [international

steel company that bought the Omarska mining complex], the

Austrians. That is neo-colonialism.

“So in a few years my human rights job will make no sense; I will be

in danger, because I will be disturbing the Bosniaks. I feel like

the last Mohican.”

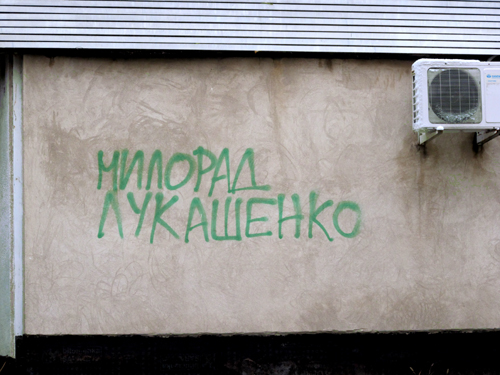

Graffiti

In Prijedor I noticed an anonymous inscription on the outside wall

of a restaurant, in Cyrillic. It read, “Milorad Lukashenko,”

combining the first name of RS President Dodik with the last name of

the dictator of Belarus.

Graffiti calling Dodik "Lukashenko "

Edin Ramulić, Izvor

Edin Ramulić is the secretary of the predominantly women’s

organization Izvor (Source). This organization campaigns for

the rights of the families of missing persons. Izvor collects

information about missing persons, advocates for the rights of the

relatives of the disappeared, supports prosecution of the war crimes

cases, and promotes public discussion of the history of the war.

This latter work focuses, among other things, on the rights of rape

victims.

Edin says, “Prijedor has the most war criminals of any single place.

There were 28 people from here who were convicted of war crimes in

The Hague, in the Bosnian court, and in Belgrade. There is nowhere

else that there were so many concentrated war crimes. And this area

has the biggest number of concentration camp survivors, and the

highest number of missing people - there are still one thousand

people missing, and sometimes there has been no DNA sample provided

to identify them.

“All of us have a relative who is missing. There were 3,173 people

who were disappeared. We created a book of the disappeared, and it

has come out in three issues, in 1998, 2000, and 2012. The first

issue was the first evidence about the missing in

Bosnia-Herzegovina. The government had done nothing.

“We followed the exhumations, helped with information. No one lived

here in Prijedor then. We got in touch with the relatives of the

disappeared. There are still remains of the missing being found this

year. We have a database. There are still one thousand missing

people.

“…The relatives of the disappeared people now have the right to the

status of family of the disappeared. This was established in Bosnia

overall in 2006, and in the RS in 2007. But there are around 500

people who have not received this status. There was a very short

time period where people were allowed to apply. Some 700 people

applied. With the status of family of a missing person one receives

a pension. In the RS it is around 140 KM; it is better in the

Federation.

“The Ministry of Soldiers deals with these cases. Mišo

Rodić is the head of the department for disabled veterans’ pensions.

He’s an assistant to Pavić. He was involved in the concentration

camps. He doesn’t deny this, says, ‘I did my job.’

“Furthermore, Mirzad Islamović was in the camps. Now, he is the head

of the department of economy. So he is Rodić’s colleague. Rodić had

the power to say who was going to be killed and who was going to get

a beating. Now, the two of them eat lunch together.

I asked, “Is this a case of reconciliation?” Edin responded, “Yes it

is, on a personal level.”

The city of Sanski Most sits on the other side of the inter-entity

borderline, in the Federation, just a twenty-minute drive from

Prijedor. When it was taken by Serb forces in 1992, Edin tells me,

there were around 700 Bosniak and Croat civilians killed. Combined

Bosniak and Croat forces retook the city in 1995, and some Serb

civilians were killed or expelled. Edin says, “In 2009 we held a

conference in Sanski Most. One Serb spoke there about crimes

committed against the Serbs when Sanski Most was retaken. But this

has never happened again.

“Prijedor has the highest number of war criminals who have

confessed to their crimes, but most of this happened far away from

here, in The Hague, so people don’t know about it. So we share that

information here, and that gives a chance for reconciliation.

At another local conference, Edin said, “Zdravka Karlica came to

speak with us from the Serb organization of fallen soldiers. Her

husband, Zoran, was killed in the war. If anyone had a reason to

hate us, she would, but she doesn’t. And there were some other

Serbs, some whose sons were killed. There was also a man who was

injured in fighting between Bosniaks and Serbs on May 30, 1992. He

was shot 32 times, and still he survived. He spoke with us; this was

a very positive story.”

Q: Are these people in favor of reconciliation?

A: “Everyone is, except for the politicians.”

“In 2011 we had a conference with Croats from the Association for

Return to the Valley of the Sana River. Hrvatski Dom. This

was a conference to help the Croats. Again, Pavić didn’t attend. His

letter said that we were working to create an ugly picture of

Prijedor. But it wasn’t us who did that; we are not guilty of that.”

There has been strong resistance to the erection of a commemorative

monument, or for that matter any other kind of commemoration, at

Omarska. One of the forms of obstruction has been cooptation. That’s

too complicated a story for me to go into here, but Mittal and the

local government, together with some outside “reconciliation

careerists,” have had considerable success in thwarting the movement

for memorialization. Meanwhile, monuments to Serb soldiers are

erected in many places. Edin reports,

“There are Serb victims, and the municipality erects monuments to

them, but none for the Muslims. The only public place where there is

a commemorative marking is at Keraterm. Within 200 meters of the

municipal building, there are five monuments to Serbs. One is to Rašković,

the Croatian Serb founder of the SDS [the Serb Democratic Party,

whose Bosnian branch was led by Radovan Karadžić].

This was perhaps placed there to please the displaced Serbs from

Croatia.”

Monument to Serb fighters placed by

wartime location of concentration camp at Trnopolje, near Prijedor

Mirsad Duratović

I met with Mirsad Duratović, the president of Sudbin’s concentration

camp survivors’ organization. Sudbin had told me that when Mirsad was

17 at the beginning of the war, Serb separatist forces killed eleven

members of his family, including his father and his grandfather,

“all in two minutes.” Mirsad survived Omarska, Manjaca, and

Trnopolje concentration camps.

Mirsad discussed the work of his organization: “There are around

4,000 registered members. 90% of them live abroad. Some of them come

here once or twice a year. There is also the Association of Kozarac

Camp Survivors, led by Sabahudin Garibović. And some of the people

from Kozarac are members of our association.

“We are mainly involved in commemorating the anniversaries of the

opening and closing of the camps. Camp survivors do not have the

status of civilian victims of the war. They have no legal status as

such. That is one of the things we are struggling to accomplish. The

issue has now been in court for four years.

“Q: What would be involved in having that status?

A: “There is some material benefit, a pension. But we don’t just

need that material benefit; we also need the recognition of the pain

in our spirit.

“In his trial at The Hague, Karadžić said

that the war started on the 30th of May, when the Croats

and Muslims attacked Prijedor. But on May 22nd, the Serbs

had already attacked my village of Biščani.

They killed my father and my fifteen-year-old brother, my

grandfather as well, and three of my uncles. I am the only male

survivor from that family. And by the 30th of May, the

concentration camps were full.

“We are not being allowed to place a monument in Omarska, nor in

Prijedor. That’s what hurts us. We need recognition from the

government that crimes happened here. There is no amount of money

that can assuage that pain. There is no law regarding a deadline to

finish this process. The other day one woman who had been in Omarska

died. Who will remember all this?

Q: What’s going on now with the campaign for memorialization in

Omarska?

A: “The main obstruction here is the city government; the mayor is

preventing it. We have contact with Mittal; they say that when the

government gives its approval, they will help. The problem is not

with the company at all.

“If the government were to permit the memorial, that would be an

admission. Now, there are six monuments for fallen Serbs, and none

for our side. There is one monument for the fallen police, another

for mailmen, another for hospital workers, and another for miners -

but these are only for the Serb members of these professions.

“There is not only discrimination here towards the dead. There is

discrimination in hiring as well. Serb veterans get priority. Their

children receive scholarships, but ours do not.

I asked Mirsad if he thought that what exists in Prijedor conforms

to the legal definition of apartheid. He answered, “The government

provides 500,000 KM for the victims of the war - but only for the

Serbs, and this is written into the law. That money goes to five or

six Serb veterans organizations. We have six organizations here of

Croats and Muslims. So this is legalized discrimination - and this

is money that partially comes from the taxes that we pay.

“They also reserve funds for the monuments to the Serb soldiers, and

to their organizations, but nothing for our side. We have a case

about this pending in the EU Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg.”

Q: Is there a complete halt to the campaign for a commemorative

monument at Omarska?

A: “We don’t know what to do. We tried to go to London for the press

conference, but we were not able to get visas.

“The international community could help us if it wanted to, as it

did in Srebrenica. But it is playing its own game. If they were able

to take care of this problem in Srebrenica, then why can’t they do

so here?

“We need to have a memorial center in Omarska, and one in Prijedor

as well. If this were to be done, then we would be able to move on.

As it is now, I do not have the right in Prijedor to commemorate the

day of the death of my parents.

Omarska mining complex, wartime

concentration camp

“More than one thousand of those who were killed have not yet been

found. There were drivers and other people who were involved, who

were witnesses. There are people who know what was done. So why

can’t they find those missing people? There are at least five

witnesses of what happened in my village who have already spoken.

Some of them have testified in The Hague - but no prosecutor has

taken any action.

“If you were in my place, what would you do? My grandmother, my

other relatives, are gone. I must look for them and find them; then

life can go on. Why is it like this? There are prosecutors in

Sarajevo, at the state level, who could do something.”

The weekend that I was in Prijedor was the time of the major Muslim

holiday, Kurban Bajram, as I mentioned in my previous report. Mirsad

noted this, saying, “Now it’s Bajram. Ordinarily, that’s a holiday

where the whole family gets together, something like Christmas for

the Catholics. But I’m sitting with my mother alone, and Sudbin with

his, and it’s sad. I don’t like this holiday.

“What have I been waiting for, for fifteen years? In ten more years

I won’t be capable of doing this work, I’m already sick from the

results of the beatings in the camps. I have problems with my

stomach, and they injured my arm.

“The people who were convicted of committing war crimes and who are

becoming active now again in politics are saying things like, ‘We

served our time, now we are free to do what we want.’”

At this point the recounting of the tragedy, the misery, and the

denial and obstruction was affecting me. I felt close to tears. I

could hardly fathom the will to persevere on the part of these

activist survivors.

I brought up something that has occurred to me, a form of

on-the-edge activism that has been practiced in the United States,

admittedly with much less risk:

Q: You are aware of the Occupy movement in the US. What do you think

of the idea of doing something like that here, for example, sitting

at the entrance to Omarska as a protest?

A: “There are not the people for that. Here there are perhaps around

5,000 people. If there were 500 of those who would participate, it

would just be a small effort. We have organized some actions,

although it is prohibited.

“There is fear. If the authorities see that your organization is

doing this kind of thing, then the government says that you are

‘rebels,’ and then you get no assistance from the municipality.”

Q: What kind of assistance do organizations get?

A: “For example, scholarships for students to go to school.

Employment.”

“We have no money; how can we pay the rent? Courage is useless in

this regard. And there have been threats against us. There is

economic pressure, and when that doesn’t work, there is physical

pressure. The saddest thing is that the police don’t do anything

about those threats of violence. And people come from the

international community, but they don’t help.

“There are people who are leaving. So they won’t talk about these

things. Whoever can leave, is leaving. Regardless of how patriotic

you are, you still have to have something to live on. (Looks out the

window at the weather) - You can’t live on snow. We have children;

they want chocolate, they want a bicycle. If you have nothing to

eat, you pack your trunks and you leave.

“In the last year there were thirty returnees who died, and no one

was born here. It’s the third year that it’s been like that. We have

three schools in the six villages around my area. There were five

schools, now there are three. When I was in first grade in Biščani,

there were 36 students in the first grade. In those six villages

there were 250 students in first grade.

“Now there are thirteen. In the different schools, there is one

student here, and maybe two there, in first grade. Next year, maybe

altogether there will be four students in first grade. When we first

returned, there were sixty students in the four-year elementary

schools. Now there are 36. Next year there will be fewer than

thirty.

“When those people reach twenty years of age, they go looking for

work - not in Prijedor, but at least in Slovenia or Croatia, or

beyond. They leave. In the last twelve years there have been

hundreds of weddings here; all of those married couples left.

“Sudbin and I were born in 1974; we are the last generation of people

who are staying here. Now the process of ethnic cleansing is

finishing. It is the same for the Serbs in the Federation. People

who are in the minorities are leaving from the smaller cities. Serbs

are even leaving from Drvar in the Federation, where they have a

Serb mayor; but they mean nothing to the Federation.

Mirsad asks, rhetorically, “Why did the OHR [Office of the High

Representative] not remove Dodik?” I responded that “the OHR gave up

on making a difference in that way a long time ago. There appears to

be no long-term plan for Bosnia-Herzegovina on anyone’s part -

except for that of Dodik.”

Mirsad commented, “Everything is going according to that plan. But

he is not acting alone.

“If you want help from the international community or the courts, or

from an Embassy, you can’t criticize them. Some organizations have

consented to those conditions. But our task is to point out our

problems - so what can we do?

“Some of the NGOs have become satellites of the government. They can

criticize the government. But they have to choose between receiving

money or being beaten.

“An Arab Spring or Occupy movement can’t happen here - there is too

much at stake. What’s going on in Greece? It’s worse here, but no

one is responding. Governments come and go, they keep stealing, and

there is no prosecution when someone new comes into power. That is

because the next person in power knows that he could end up in the

same position.

“We lack the critical mass for a rebellion. The government keeps a

good eye on potentially active people - and buys them off if

necessary.”

Kozarac

Back in Kozarac, I fit in a couple of quick conversations with local

folks who have been active, since the end of the war, in rebuilding

their lives and in rebuilding Kozarac. I wrote about the work of

activist and camp survivor Švabo in 2010.*

With his organization Optimisti, Švabo has been active in the

struggle for memorialization. Among other things, he has traveled

and educated himself about the nature of other memorials, especially

those related to the Holocaust. He has gone to symposia at Auschwitz

and at Dachau. He says, “We need to have an entire concept of

a memorial center. That has to include even the restrooms, and there

must be a director, a memorial section, a film room, and an

archives, and so on.” But, as mentioned, all this is blocked for

now, in one way or another.

“Meanwhile,” Švabo says, “we can

have a web site. Other memorials have a web site to augment the work

of their centers; we can start with one.”

Regarding the stalled struggle for a

memorial at Omarska, I asked Švabo whether he thought it

would be possible for people to mass at Omarska, something like an

Occupy action. He did not want to be pessimistic; he said, “Local

people here aren’t prepared to mobilize for something like that. But

I think something like that action could be done…”

Švabo turned to the problem of outside

support for Kozarac. “There were 22 weddings here in one day,

all from the diaspora. There were 7,000 people present. People in

the diaspora come here for vacation, but they are letting go…”

The international community and the relevant court at The Hague have

restricted all discussion of genocide to Srebrenica, while genocide

arguably occurred in many parts of Bosnia-Herzegovina - certainly in

Prijedor and in Višegrad. People

who survived the destruction of the Bosniak communities outside of

Srebrenica need recognition of their experience just as much as do

those from Srebrenica.

Švabo said, “If there was not

genocide in Prijedor, then there is no such thing. I carry that

genocide on my shoulders - I was in the camps, I saw the beatings

and the killings. So I don’t need there to be a decision in order to

know there was genocide.”

War memorial to civilian victims,

Kozarac

I spoke with my old friends Emsuda and Osman Mujagić, who were among

the first to return to Kozarac in 1998-1999. Emsuda told me that

there were around eight thousand returnees to Kozarac and the

surrounding villages (out of a pre-war population of 27,000), and

overall in the Prijedor municipality, around 24,000 returnees -

“though people have left. Now there are fewer people. People came

back, saw that there was no work, and left again. Young people are

leaving.”

Srcem do Mira, a women’s organization founded in 1993 in exile,

actively participated in the uphill struggle for return to Kozarac

in the postwar period.* In the first years after return, the

organization was involved in a wide range of issues from education

to a crafts cooperative to various kinds of training. Now, Emsuda

says, Srcem do Mira has reduced its projects, as other organizations

have formed. “Now we mainly work with older women, in psycho-social

activities. And we help younger women prepare to start a business.

Other organizations that use the Kuća Mira include sports groups,

the cultural-artistic association, and the hunting club.”

In recent years Emsuda had described to me various kinds of

harassment that returnees to Kozarac had suffered at the hands of

the local authorities. I asked if this kind of treatment was still

going on. Emsuda told me about an investor, a Kozarac returnee from

Norway who “three years ago invested a million KM in a cattle farm

where he wanted to produce healthy food and bio-fuel. Throwing

mountains of paperwork at him, government has still not given

permission to run his company, so he can’t hire anyone.” The entire

Bosnian-Herzegovinan economy is shackled by this kind of red tape,

discouraging much foreign investment. But it can particularly be

felt as discrimination in the return communities.

And it sounds like there is real economic discrimination in Kozarac

that overcomes any other possible explanation: “There is all kinds

of harassment, still. The finance inspectors come to the local

businesses. There, the cash registers are electronically connected

to the tax agency. If there is more or less money in the register

than there is supposed to be (based on sales), then the owner can be

fined 500 KM. And one owner was fined 500 KM for not having the box

that the cash register came in.

Q: Why can they fine someone for not having the box?

A: “Because there wasn’t something else to fine them for. But they

don’t bother the Serb businessmen about this - they don’t even have

to have a cash register.”

Mosque in Kozarac

Leaving the Krajina

I could have stayed in Prijedor, and revisited Banja Luka. There

were more people to talk to, interesting discussions to be had -

maybe even some uplifting ones. But at this point I was chilled to

the bone. I stopped by a Chinese store and bought a cheap but warm

scarf, a pair of long johns, and thick socks (“rabbit hair?”), but

this did not warm the chill in my spirit, the building annoyance,

the sympathetic frustration, the anger. Even seeing the name

“Republika Srpska” painted on the trains irritated me. I had to

leave the RS. I had to get out.

One last unhappy experience, of my own making, awaited me at the

Banja Luka trainyard. There, on the periphery, was an older man

selling cheap goods. His stand was dominated by t-shirts bearing the

picture of Draža Mihajlović and other Chetnik

propaganda (see my discussion of the movement to rehabilitate World

War II royalist Mihajlović in my last

report). Although I knew that this t-shirt was widely available in

the RS, seeing it now got on my nerves. I should’ve kept my mouth

shut. But, remembering what Dražana said [see

my previous report], I said to the man, “So, fascism is cool now,

huh?” He answered, “What, where do you see fascism?” I said, “Here,

all around you.” I walked away.

At this the man started yelling to everyone (except, fortunately,

there was no one around) and, tentatively, walking towards me. I

kept walking and ignored him, and he subsided.

I knew that my comment was not going to do any good and that I

should have either just moved on or tried something different. My

bad mood wouldn’t allow me, but I could have asked him, “Tell me,

what do you like about “Draža Mihajlović?”

Or maybe I should have asked, “Do you have any Hitler t-shirts?”

*

Back in Sarajevo, I talked to Dževad and

reminded him of his earlier comment: “I can’t believe that in Banja

Luka they don’t know what happened in Prijedor.” I told him that I

had mentioned this to two young activists in Banja Luka and they

said that people don’t know, and that there are only a couple of

places that you can get Oslobodjenje or Dani in Banja

Luka, and that what is mostly available are propagandistic media

such as Glas Srpske, Nezavisne Novine, and Blic.

Dževad said, “They have access to every TV

station, etc, how can they not know?”

I said, “It’s the same problem with us, people don’t know that the

US killed two million in Southeast Asia, and now some hundreds of

thousands in Iraq, and then Afghanistan, and then the drone planes

killing civilians in Pakistan, etc…”

Dževad: “But those things are taking place in

another country, this was right next door, you could see the houses

on fire!”

“…And now, whenever I meet a Serb policeman, he hurries to tell me

that he was not involved in ‘those actions.’ Yes, they were all

cooks. The army was full of cooks.”

*

And I talked to Hikmet about the same issue of ignorance versus

denial in Banja Luka. He said, “In Banja Luka they had to know about

what happened to the Ferhadija mosque, at least. It was blown up.

Then the bulldozers came. The mosques were plundered and torched,

and then even the stones from the mosques were cleared away. It

wasn’t just individuals who did this. This was done officially.”

Srebrenica Results: More Delay

The vote count from the Srebrenica municipal elections was known

almost a month ago: 4,455 valid votes for Muslim candidate Ćamil

Duraković, and 3,663 for Serb candidate Vesna Kočević. The official

results from all the municipalities were confirmed last week, just

before the one-month deadline - except for a few. There were a

couple of municipalities or, in some cases, polling districts, where

chicanery was revealed and the vote will be repeated.

Nor was Srebrenica’s result confirmed, but this was different; the

“Coalition for the Republika Srpska,” representing the parties that

supported Kočević, filed a complaint with the Central Election

Commission. Chair of the Commission Branko Petrić supported the

complaint and proposed that the elections be annulled due to

“irregularities and infractions,” but he was outvoted by others on

the Commission. However, now the Coalition is taking its complaint

to the Court of Bosnia-Herzegovina, so nothing is certain.

***********************

*For previous writings relevant to these topics, see the following:

Some

of my early writing on Emsuda Mujagić’s work with Srcem do Mira

(see issues 2 through 10)

Kozarac and Prijedor, 2008

Kozarac - Prijedor, 2010

Remembering Mladen Grahovac

Index of previous

journals and articles