ACTIVISM IN

SARAJEVO

What needs to be the target of activism in Bosnia? In my series of

reports so far I have particularly focused on the campaign for

memorialization of the war crimes that were committed. It is my

opinion that for justice to be achieved, the atrocities that people

endured have to be recognized; the criminals have to be legally

processed; and the victims have to have the possibility of

commemorating the history of their suffering publicly.

There will be more discussion of these things. But there are also

other targets of activism. The protest against the destruction of

Picin Park, as described in my fifth report, in fact opened the door

to protest against corruption, profiteering, and cronyism. And these

phenomena are what’s really behind all the other problems in Bosnia

– even behind the historical revisionism and denial as well.

Grassroots activism occupies a small place in the modern history of

the country; the dominant model for political change is top-down.

Non-governmental organizations, often called the “third sector,”

tend to replicate this hierarchical model, sometimes in the extreme.

While the personality cult of Tito is gone, the rule of one “big

man” has often simply been replicated at lower levels – from the

local party boss all the way down to the bus driver. NGOs exist

along an entire spectrum from the altruistic to the profiteering.

For the most part, their relationship to activism is tangential.

Activism in Bosnia-Herzegovina has its ups and downs, and developing

a grassroots movement in Bosnia is a matter of reinventing the wheel

in very adverse conditions. It is not unusual for an independent

project to arise in one location, where it will last a while, and

then either cooptation by authorities or lack of skilled leadership

will lead to its demise.

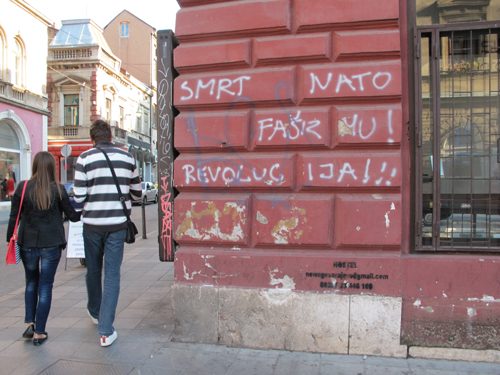

"Death to NATO Fascism! Revolution!"

Graffiti in Sarajevo.

I spoke with Darjan, a Sarajevo activist with the organization

Akcija Građana (Citizen Action), and formerly with Pokret Dosta (the

Enough! movement), which I have described before. Darjan mentioned

the height of grassroots activism in Sarajevo, which took place in

February of 2008. At that time, somewhere between six and ten

thousand people came out to participate in a march in protest of an

epidemic of street violence in the city. Not long before,

17-year-old Denis Mrnjavac had been stabbed to death by unknown

attackers while he was traveling in a streetcar. There were many

other such lethal or dangerous incidents that had taken place in

that period. Pokret Dosta was the leader of this protest, along with

several other protests in the year or so before and after that event

(See

http://balkanwitness.glypx.com/journal2008-2.htm).

As with the activism around Picin Park in Banja Luka, protests about

the street violence were an entrance into protests about other

grievances such as utilities price hikes and, generally, about

corruption. Dosta built a network in several cities around the

country. Unfortunately, the movement lost momentum and today, if it

exists at all, its activity has been reduced to the painting of

graffiti around Sarajevo.

Darjan said, “I split from Dosta because I saw that there was

decreasing interest in actually changing things.” He mentioned that

at its height, Dosta had “about fifty good activists.” But he

faulted the leadership for lack of transparency.

Discussing the situation of activism on a larger scale, Darjan said,

“The problem in Bosnia is that we’re not one society. We have the

societies centered around Banja Luka, Sarajevo, and Mostar. And the

public opinion that could influence the government does not exist…

There is not a network established for collaboration among people.”

“There are problems in organizing and promoting change. The Serbs

from Sarajevo went to Višegrad,

Pale, and other places. Many villagers came to Sarajevo. They think

that things are great for them here, because they have running water

and other amenities. They don’t know that they have the right to

call for more.”

“In 2008 there were the demonstrations, and afterwards there were

four people who lost their jobs because of being involved in the

protest. There were a couple of people who had been working in the

tourist industry; they lost their jobs.

“We held preparatory demonstrations to the big one for three months,

every weekend. There were marches. In that time, there were never

more than three thousand participating. Meanwhile, there were always

more than that number in the kafanas of the city.

“At one point in the demonstrations some people threw some rocks.

[One of the leaders] called for people to go home. That was the end

of it. He should have organized people to come back, to continue the

protests.

“Safety on the street is a big problem. But if the Reis [the leader

of the Islamic community] called for a protest because people are

eating cvarci [fatback, a pork product], there would be more

people on the street. As activists we are outsiders, marginalized.

And meanwhile, in the schools they are not teaching critical

thinking.

“In Western Europe after World War II, democracy developed. People

had more rights, and women’s rights improved too. Here after the

recent war, they did not even prohibit those who started the war

from participating in politics.

“The first post-war election took place in 1996 - that is

unfathomable! They gave the election to the idiots. And since then,

we’ve been running around in the same circle.

“As for those leaders who keep being elected, they are not actually

in favor of Bosnia-Herzegovina becoming part of the EU, because then

rule of law would be implemented. And they would be the first to go

to jail.”

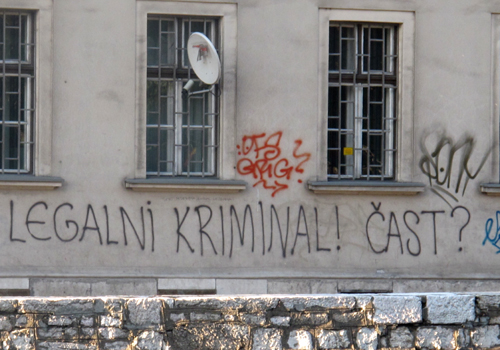

"Legal Crime - Honor" Outraged graffiti,

Sarajevo

I asked Darjan about the work of Akcija Građana.

“We started as an informal group, working on that basis for six

months in 2008 without registering. Then, we had a referendum within

the group about registering. I was not in favor of registering, but

we did. By registering, we legitimized the system. And they are the

ones who make the rules of the game. Then, we got support from the

Open Society Fund - but they don’t try to influence us.

“We were arrested at Butmir base [headquarters of the EU military

operation in Bosnia, on the outskirts of Sarajevo] when there were

the negotiations there in 2009. They held nine of us for two hours.

We displayed a banner that read, ‘For us, it’s fine this way’

[satirizing the position of the leading politicians]. That is, it’s

fine for them if we remain in this black hole, where money

laundering is common, as are trafficking of drugs and women, and the

leaders can take pleasant vacations.

“We had gone to Butmir a couple of days in advance to let the

authorities there know that we were going to come and make a

protest. They showed us an area where they were going to let us

stand. But when it came to the demonstration, it didn’t work out

that way. We were arrested. But the media never covered this, not

even for one minute of air play. They just weren’t interested.

“Now our work is going slower, and there is a lack of results. We

have decided to orient ourselves towards high school students, doing

workshops with them. Then, once these people come to the University,

there will be activists. As it is now, activism is weak and there is

no action. In Sarajevo there are about 3,000 students in the

University. If there were that many activists, it could be enough

for a revolution, a strike at the system.

“We had a chance in 2008, but we didn’t know what to do. They called

us mercenaries.”

Q: Are there any effective NGOs working in Sarajevo?

A: Activism can exist in an NGO. But for now, the NGOs are only

involved in humanitarian work. The majority of the NGOs are family

arrangements.

[I am conveying Darjan’s opinion here; I don’t mean to dismiss some

Sarajevo NGOs that are actually quite effective in their areas of

focus.]

Q: What are the themes of your discontent now?

A: We are calling for responsiveness. For example, in Sarajevo the

water supply lines, the transportation, and the security situation -

these are all in disastrous shape. There are guns and knives on the

streets, stabbings in the streetcars. The cultural institutions are

deteriorating too: The museums, the libraries, the galleries are all

closing. Even in the war it wasn’t this bad.

“All the aid gets stolen. They steal from the state companies, and

from the state budgets; then they build villas for themselves.

Seventy percent of the funds from the IMF go to pay pensions and

salaries rather than towards investment. We are headed in the

direction of the situation in Greece.

“We have wasted a good opportunity to make progress, to make a

European city of Sarajevo, instead of the biggest village in the

country. People here do not accept others, different people. We have

lost our educational system, our health system, and our morals.

Then, we have taken the worst from the West and from capitalism:

corruption, the bad health coverage. …When I come from Vareš

to Sarajevo, it is like coming to a different world.

“There can be no revolution here. All the state companies are here,

so there are well-paid people here. Those who work for the companies

vote, and the large number of marginalized people do not vote. Nor

do many of the women vote either.

“Educated people have left here. Out of 35 people from my elementary

school, there are six who have stayed. Of 32 from my high school, 15

have stayed. I am 34, so half of my life has been spent in waiting,

watching from one election to another.

“There is much poverty, but people are religious. They say, “Ako Bog

da [If God grants].” And I ask a villager, “Did God ever give you a

cow?” You won’t get anything, if you don’t do anything.

“Discontented people in the city are inclined to torch and wreck

things, not to build things. We simply haven’t come back to our

senses here. Gras [the city’s public transportation company] raised

its prices. There was talk of a boycott, but it didn’t lead to

anything. In Sarajevo there is more involvement in drinking coffee

and in betting than in activism.

“If someone comes to Sarajevo they notice these things: beggars, the

ruined buildings, and the shiny new glass buildings.”

For more on Akcija Građana, see

http://www.akcijagradjana.org/.

Graffiti in favor of gay freedom,

Sarajevo

RETURN TO SREBRENICA

During my time living in Bosnia-Herzegovina between 1997 and 1999,

and for several years afterwards, I paid close attention to the

return of refugees and internally-displaced persons to their pre-war

homes. For approximately seven years after the war, return was the

most important and compelling movement, from the grassroots on up.

International and domestic leaders were themselves pushed and

prompted by movement from the grassroots. Intelligent (and sometimes

charismatic) people who had been high school teachers, social

workers, or office workers before the war were galvanized to lead

their communities back home. People like Zulfo Salihović, Hakija

Meholjić, Vahid Kanlić, and above all Fadil Banjanović “Bracika”

stood out as the individuals who expressed the determination of

their constituency to achieve their right to return.

Return essentially wound down ten years ago, with few exceptions.

Some return took place in nearly every one of the 140-odd

municipalities throughout the country, but in many cases it was mere

symbolic return. There were places where there was almost no return;

other places where, say, twenty percent of the displaced returned,

and a few places, such as Prijedor and Zvornik municipalities, where

there was a truly significant amount of return, approaching fifty

percent of the pre-war population.

In Srebrenica return took place late, and it was weak. On the other

hand, in nearby Zvornik, significant return took place in nearly

every village in the municipality.

It is interesting to compare the two returns. I won’t go into great

length on this here, but I will share a couple of points of

comparison, and then some of the observations of journalist Hasan

Hadžić, who was closely involved with Bracika in the return movement

in northeast Bosnia from the beginning.

I have written at length about return to Srebrenica

here

and I have written before about Bracika

here.

First of all, return to Srebrenica was fiercely obstructed by the

Serbs who controlled that municipality. In response to this

obstruction, the international community placed sanctions on

Srebrenica, and basically turned its back on the town for several

years. Meanwhile, it was difficult in any case to mount a movement,

because the male population was decimated. There were survivors, but

among them there were also some 6,500 single mothers. The

overwhelming number of families without male heads made it difficult

for potential returnees to prepare to clear the rubble from

devastated property and to plan to rebuild, let alone to do any

extensive farming.

A devastated house in Srebrenica

These things are obvious. But behind the scenes, I had periodically

been hearing about obstruction against return from the other side –

from the leaders of the Muslims within the Croat- and

Muslim-controlled Federation, where hundreds of thousands of

displaced people from the Republika Srpska had taken up temporary

residence during the war. I heard, even from former members of the

Muslims’ ruling SDA party, that members of the SDA were acting to

discourage people from returning to Srebrenica.

The apparent reason for this was that it was useful to the SDA to

have what was called a stable, ethnically-homogenized “voting

machine” present in the Federation, in order to keep that party in

power.

Meanwhile, Bracika and his fellow activists, early on, were putting

themselves in harm’s way to establish a foothold for return in the

outlying villages of Zvornik municipality. This movement began

almost immediately after the war’s end.

It helped that those villages were right across the inter-entity

borderline from the Federation, thus relatively easily accessible to

would-be returnees. On the other hand, displaced Srebrenicans had to

travel across many kilometers of hostile territory, at quite some

danger, in order just to visit their pre-war homes.

Hasan Hadžić spoke to me about his work with Bracika, about the

various manifestations of obstruction to return, and about

differences between return to Zvornik and Srebrenica.

“Bracika was my brother. The strongest movement for return was here

in Tuzla.

In 1996, in Tuzla, we formed the office for return, while in

Sarajevo they were doing the opposite. We exerted pressure in 1996

to create that office.

“We were in Sapna [in the Federation] and we could see them blowing

up houses right next to Sapna, in Jušići

[a village in Zvornik municipality, in the Republika Srpska, where

some of the first return efforts took place].

“On the Serb side, authorities were spending money for the displaced

Serbs to stay in the Republika Srpska. They built hundreds of

settlements, for example, they built one at Branjevo [site of one of

the Srebrenica massacres]. They spent millions on this.

“In Jušići we went step by step.

There were special [Serb] police forces who were drawing guns on us.

They beat older people and women who were staying in one return

house. Then some of our people started throwing rocks at the police

and defending themselves with toljage [clubs]. When this

happened, the IFOR [UN troops] troops came in a transport vehicle.

It was exciting.

“During our early return attempts, they killed a man in Gajevi near

Koraj, near Lopare. They shot at our column of people. This was in

the fall of 1996.

“At the higher levels, there was a General in IFOR who criticized

us, saying that we were a ‘military operation.’ But it wasn’t true,

of course. At the middle level of IFOR there were Majors who

understood us better and knew this was not a military operation, and

they supported our drive for return. They patrolled and helped. When

we returned to Mahala, our men were coming with clubs and rocks. We

knew we could fight because the IFOR soldiers were behind us.

“That General was telling us to go slowly. But you can’t, it would

not have worked. Bracika had a tactic: first we went to clean the

cemeteries. If we had waited for permission, it would never have

happened.

“People were already leaving the country, and we couldn’t afford to

wait. So we took those risks. Then other people around the country

saw what we were doing and that it had worked, and took similar

moves, such as in Goražde.

“One of the differences between Zvornik and Srebrenica was Bracika.

But the government really never supported return.

“Bracika was a man of the people. He returned with his daughter and

put her in the school with the Serb children. Sadik Ahmetović

[former vice-mayor of Srebrenica] never did that. Neither did

Šefket Hafizović or Hasan Bećirović

[other highly-placed SDA officials from Srebrenica]. They would come

to Srebrenica like tourists for two or three days and then return to

Sarajevo for džuma [Friday prayers].

“But Bracika’s returning, with his daughter, sent a strong signal to

the displaced people that he was sincere. There were 700 people who

were killed in that area, but return still happened!

“More people returned to two or three villages near Zvornik than to

the whole Srebrenica municipality. But Srebrenica is the cash cow.”

By this, Mr. Hadžić meant that a disproportionately huge amount of

international resources for return and reconstruction went to the

Srebrenica municipality. In my own opinion, this took place because

the international community, in its various forms, somehow decided

to expiate its guilt for the destruction of Bosnia-Herzegovina

particularly in Srebrenica, while ignoring the possibility for

recovery in some other parts of the country. So large amounts of

international aid were channeled to that area (and even larger

amounts promised). An arguably huge amount of that aid never reached

the people it was intended to help.

Speaking of the return effort to Srebrenica, which started in

earnest in 1999, Mr. Hadžić said, “Hakija [Meholjić, wartime police

chief in Srebrenica and a postwar leader of return] was returning

people, and Adib Djozić was coming out in a jeep and scaring people,

saying ‘They will kill you.’ Then people would go back where they

were. Djozić worked for the Ministry of Refugees in the Tuzla

Canton.

I asked Mr. Hadžić about statements I had

heard to the effect that the SDA, in the early period of return, was

trying to dissuade displaced Srebrenicans from leaving the

Federation and returning home. He answered, “We went to Vozuća with

Hakija and Bracika to encourage people to return to Srebrenica. Then

Djozić and Bečirović came in immediately after that and broke things

up. Having people return didn’t suit them.”

When people talk about encouraging return today, they mean making

the return that has already taken place sustainable. Because of

discrimination and difficult economic conditions it is not uncommon

that people who have returned will pick up and leave again, as I

have previously described – preferably for another country.

Returnees to Srebrenica

On this issue, Mr. Hadžić said, “Return has

ended. There is much money for sustainable return that has come to

the Ministries, but none of it is getting to the actual places of

return. It is being spent on things unrelated to return. For

example, the authorities in Sokolac used money for return to fix the

water supply system. And in Prusac they fixed a road. Neither of

these things was related to return communities.”

For English translations of a couple of Mr. Hadžić’s

articles, see

http://www.ex-yupress.com/dani/dani6.html

and

http://www.ex-yupress.com/dani/dani112.html.

ACTIVISM IN PRIJEDOR, REVISITED

In my sixth report, I wrote about events in Prijedor municipality,

in northwestern Bosnia (see

http://balkanwitness.glypx.com/journal2012-6.htm).

Prijedor municipality is a special and important place in

Bosnia-Herzegovina. The crimes that were committed there during the

war reached extreme heights in the terror that they spread.

Thousands of people were tortured or murdered, and many more

expelled.

These things happened in many parts of Bosnia. But Prijedor is

special for another reason as well. Expelled citizens of the

municipality were in the forefront in return to their homes soon

after the war. And because there is that returnee population – and

because some of them are brave enough to represent their community

in the face of repression, and to fight for the rights that they

know they have – Prijedor municipality happens presently to be one

of the most active locations of human rights struggle in the

country.

Because of this, and because of the wrongs that were committed in

the municipality during the war, it is important that people who

believe in solidarity around the world support Prijedor. Those who

care about Bosnia-Herzegovina should notice Prijedor, should pay

attention to what is going on there, and should find out how to

support that struggle.

People occasionally say, “Too much support and resources went to

Srebrenica, to the detriment of Prijedor and other places in

Bosnia.” I would not say that there has been too much attention upon

Srebrenica, but there has simply not been enough support or

attention to Prijedor and other places. It is as if the world,

especially international officials who make decisions about

allocation of resources, expiated their guilt on Srebrenica, and

then turned their backs on the rest of the country. Well, we don’t

have to do the same thing.

There is news on the human rights front in Prijedor.

At the beginning of December, a “Committee for Commemoration of the

Twentieth Anniversary of the Mistreatment of Innocent People of

Prijedor Municipality,” composed of eight local non-governmental

organizations, announced a plan to hold a demonstration and march in

protest of ongoing discrimination against Croat and Bosniak

survivors of the war. The event was announced for International

Human Rights Day, December 10th (the anniversary of the

UN’s 1948

Universal Declaration of Human Rights).

Here’s part of what the Commemoration Committee wrote in its

announcement: “Employment that was forcefully taken away [from

expelled citizens of Prijedor] has not been restored; the municipal

government invests the least amount in (returnee) settlements where

the infrastructure and all buildings were completely destroyed. The

discrimination against civilian victims is particularly obvious. The

possibility for them to achieve any of their rights is obstructed in

every manner. The municipal budget apportions funds exclusively for

the Serb soldiers and their associations. Monuments are pointedly

erected to fallen Serbs in public places, in front of schools and

institutions, in a way that intimidates members of the other

ethnicities and minorities. The government has erected a terrifying

monument to Serb soldiers at the place where thousands of women and

children from Prijedor suffered, at Trnopolje camp. At the same time

it forbids the construction of any commemoration at the largest

places of suffering and torture in Prijedor municipality, notably

the death camp at Omarska. In the city itself there is not even the

smallest marking that would commemorate the suffering of non-Serb

civilians. (…) A particularly grave rights violation has been noted

against more than a thousand disappeared Prijedorans. Besides all

other human rights, they have been denied the right to identity and

to a dignified burial.”

This announcement was posted on December 5th. On the 8th,

it was announced that the Prijedor police department had prohibited

the march component of the action.

The Commemoration Committee protested this prohibition, mentioning

that, on May 23rd, the police had forbidden the

organizations of returnees and war survivors from marching to

commemorate the wartime murder of 266 women and girls in Prijedor

municipality. In response to the banning, the Commemoration

Committee accused the Prijedor government of repression and of

promoting apartheid in the municipality. A statement also recalled

the wartime murder of some 800 prisoners at Omarska and Keraterm, as

well as of 200 more prisoners killed in a massacre at Korićanske

Cliffs.

Following the prohibition of the demonstration, the police also

called some of the event’s organizers for “informativni razgovor,”

or interrogation. The Commemoration Committee vowed to resist the

repression and these grave violations of rights. Edin Ramulić,

activist with the Prijedor association “Izvor,” refused to respond

to the police’s invitation to interrogation.

Ramulić stated that there was no point in cooperating with the

police, when their dictates were inconsistent and made no sense. In

May activists had been prohibited from gathering on the town square,

with the excuse that the situation was “not favorable for security

considerations.” Now the police department was saying that they

could gather, but would not be permitted to make a march of one

hundred meters down the pedestrian zone and back.

Ramulić further commented, in connection with previous appeals of

such rights violations, that “going into a legal process makes no

sense, because there are no sanctions.” The activists had appealed

to the Ministry for Human Rights and Refugees, to the OHR, and to

foreign Ambassadors, all without results. Foreign officials had even

addressed the problem with Mayor Pavić, but the repression – and

attacks by extremists – just worsened.

Ramulić also noted that even Bosniak members of the municipal

council for

whom returnees and survivors had voted turned against them. They did

not work to defend the activists, and some of them tried to persuade

the activists not to use the word “genocide” in their public

statements. Earlier this year, Mayor Pavić had prevented a

demonstration and threatened prosecution of activists because of

their use of this word. Ramulić said, “Some of those politicians are

close to those who rule the RS; probably the explanation of this

[behavior] is that they are prepared to do anything in the interest

of their own political privilege.”

It is not unusual to hear phrases from activists in Prijedor

characterizing their Bosniak representatives on the municipal

counsel as “collaborators” and “sellouts.” Some of those officials,

upon the banning of the march, gave mild statements to the effect

that, “We will get to the bottom of this.”

Amnesty International

condemned the banning of the march, as did several domestic

human rights NGOs.

When International Human Rights Day arrived, some of Prijedor’s

activists decided to march in spite of the ban. Seven young people

walked through the snow, with tape symbolically covering their

mouths, carrying a banner that read, “Where human rights are

violated, civil disobedience is a duty.” Of the marchers, two were

Bosniaks from Prijedor, and two were Prijedor Serbs. There were two

Bosnians from Slovenia who marched in solidarity, and one from

Sarajevo.

In nearby Banja Luka, members of the human rights organizations

Oštra Nula and the Helsinki Citizens Assembly stood prominently in

the main square in solidarity with the activists of Prijedor. The

Prijedor Commemoration Committee held a news conference and stated,

“On the international day for the protection of human rights, the

police in Prijedor have placed themselves above the law on public

gatherings in the Republika Srpska and have prohibited a peaceful

march, without any legal basis. The police have shown that they work

according to the dictates of the local government and that they are

an important instrument in the establishment of apartheid.”

Meanwhile, RS President Milorad Dodik marked Human Rights Day,

saying that “in recent years the Republika Srpska has created an

environment in which all of its citizens can realize their human and

civil rights, as foreseen by the European Convention on Human Rights

and other international documents. We have succeeded in achieving

high standards and we will continue to do all that is necessary to,

first of all, improve the economic and social position of citizens,

which will be our priority in the coming years.”

One of the Prijedor marchers, Emir Hodžić, wrote a statement shortly

after the action, describing his position: “If the right to free and

peaceful gatherings is guaranteed in the constitution of

Bosnia-Herzegovina and the constitution of the Republika Srpska, who

has the right to violate that right? Once again the Prijedor police

have tried to show, on the day when the entire world celebrates

human rights as the heritage of civilization, that

Bosnia-Herzegovina is an absurd state…”

Speaking of the action of the multi-ethnic group, and the response

from local citizens, Hodžić wrote, “As a Prijedoran, I saw in front

of me concerned citizens, not Serbs nor Bosniaks. I saw the faces of

people who see and know that discrimination on an ethnic basis or

the prohibition of association lead to nothing good, and at that

moment, I felt hope. I felt that I was among my people, that we all

speak the same language, and that we all understand the difficult

path before us.

“Our symbolic civil disobedience echoed around the country. Our

fellow citizens from Banja Luka…heard and conveyed the message by

going out onto their streets. Various associations and workers for

human rights around the country also sent support and solidarity.

Again I felt hope, again I saw my people. We understood each other.

The full article by Hodžić is available, in Bosnian,

here.

An article showing a photo of the march, with an accompanying video,

is available

here.

Shortly after the protest action in Prijedor, the Society for

Threatened Peoples, based in Göttingen Germany, posted an “Appeal to

Members of the EU Parliament, the Council of Europe and the European

Union Agency for Fundamental Rights in Vienna.” The Appeal, signed

by Tilman Zülch for the Society, and Milada Hodžić for the Prijedor

organization Izvor, was sent to seven hundred officials of the

European Union, to the OHR in Bosnia, and to the Bosnian Ministry

for Human Rights and Refugees. It was also sent to the mayor of

Prijedor and the president of the RS. It is available in English

here.

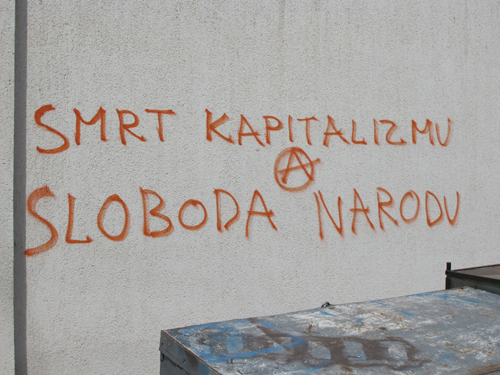

"Death to Capitalism - Freedom to the

People" Graffiti in Prijedor

While the action in Prijedor was taking place on Human Rights Day, a

more general action was undertaken in Sarajevo, Banja Luka, and

Mostar. In these cities activists from the regional NGO Youth

Initiative for Human Rights staged mock burials, complete with

coffins and a funeral march, to bury the human rights and freedoms

that they say no longer exist in Bosnia-Herzegovina.

*

On December 19th, in Sarajevo, a dozen young people staged a

mock protest against the end of the world, slated for December 21st.

Five hundred people signed onto their Facebook page. In a statement,

the group explained, “We have gathered here today in order to make

fun of some people, especially the Americans,” adding that there was

no chance that the world was going to end. The protestors proved

this assertion by displaying a can of liver paté whose expiration

date was marked as the year 2013.