MARŠ MIRA

The anniversary of the fall of

Srebrenica and the massacre committed there is approaching. On July 11th,

1995, extreme Serb nationalist forces took over the eastern Bosnian

enclave, which had been declared a “safe zone” by the UN. In the end,

the UN did not defend Srebrenica.

Tomorrow I will hit the trail -- literally -- on the “Marš mira,” or

“March of peace.” This hike goes from Nezuk, near Zvornik, to

Srebrenica.

Upon the fall of Srebrenica in mid-July of 1995, thousands of people

fled to nearby Potocari to seek protection where the Dutch UN troops

were located. Meanwhile, many thousands of men of military age,

expecting that they would be killed if they fell into the hands of the

Serb forces, headed for the woods. They walked in a column towards

government-controlled territory, roughly in the direction of Tuzla. Out

of somewhere between ten and fifteen thousand men and boys,

approximately five thousand survived.

The Marš mira traces one of the routes of escape taken by those men. It

runs 110 kilometers (about 70 miles) and is to be traversed in three

days. This is the fifth year of the hike. Last year, over four thousand

people, from all over Bosnia-Herzegovina and abroad, participated. This

year, the fifteenth anniversary, should see at least as many people

involved. The Bosnian army helps to coordinate the hike, providing tents

and food.

I am hoping that I will be able to take the march from beginning to end.

When I was a bit younger I used to do hikes of twenty miles a day, say,

in the Appalachians. But I am a bit older now. I am hoping that what I

may lack in physical endurance, I will compensate for in determination.

Some people may consider such visits to Srebrenica as “war tourism.”

That is probably true for some people, but participating in this march

is important to me because I consider it an act of solidarity with the

survivors and remembrance of the victims.

In an Internet center, I met a woman from Podrinje (the eastern Bosnian

region), from Han Pijesak, not far from Srebrenica. She told me that she

has 22 relatives buried in the memorial cemetery at Potocari. She is

going to make the march.

Elsewhere I met a man from Vlasenica, also in Podrinje. He had hiked out

in July 1995. He was one of the lucky ones -- very lucky, in fact, as he

arrived at the safe end in a week. Some people were lost, or stuck in

dangerous places, for a month or even more.

He told me that he had been hit in the face by shrapnel during the war,

and that the tip of his nose was torn off. The Americans performed

reconstructive surgery, and the faint line that showed where his nose

had been repaired was only noticeable after the man pointed it out to

me.

The man from Vlasenica told me that he ate slugs and leaves in order to

survive during the escape. He swore that he would never participate in

the march, that the one experience, coming out, was enough for him. But

some people who made the march out in 1995 are repeating the march the

other way.

“THE QUESTION”

There is one question that

everyone who comes here and thinks about this beautiful and tormented

little country asks, in one way or another: “What can happen that will

save this country and make things work?”

This is my question as well, and I have been approaching it from every

angle, and trying to listen to as many people’s evaluations as possible,

trying to weigh them and compare them. There are few conclusive answers,

other than the vague “time will tell.” But there are indications, and

some concurrence of opinion among intelligent and informed people. I

will share some of these opinions here.

This is a complicated country. A lot happens behind the scenes and there

is much information that never sees the light of day. It has occurred to

me that my search for solid, viable analysis is hindered by the fact

that many people have not only too little information, but too much time

-- a bad combination. Some people are tempted into “kafanski razgovor”

(coffee-house conversation), which is full of conjecture, and short on

facts. This pursuit is even more popular than football.

There are roughly three factors that can influence the future of Bosnia:

the domestic politicians, the international community, and the people.

Put simply, at present the politicians are not interested in giving up

their profitable positions or changing their behavior. The international

diplomats have behaved with carelessness and ineptitude, with certain

honorable exceptions.

Given this, I have directed my attention towards the activism of the

ordinary people. There, I see three main segments:

First are the organizations fighting for “truth and justice,” that is,

apprehension and prosecution of the war criminals; establishment of

memorials for the victims; and exposing the facts about wartime events.

Second, there are the NGOs that provide social services to people who

are neglected or discriminated against by the government. Sajma’s “Women

Can Do It” in Banja Luka (see my first report) is one of those.

Third, there are the local grassroots groups, often not even registered

as NGOs, that are demonstrating, agitating, collaborating across ethnic

boundaries, working against segregation, corruption, and historical

amnesia.

These three groups, in varying degrees, are part of the solution. I have

placed my hope in these activists. However, after talking to dozens of

people in the past month and a half, I am bending towards another

conclusion. Many people have told me that there is no “movement for

change,” and that the change has to come from within the political

structure. Or that it has to come from the international community. In

any case, it is clear that change is a matter of a generation or two,

not a year or two.

I am coming to the conclusion that, while the grassroots is crucial, I

have placed too much hope in the possibility of change as prompted by

what people here call the “civil sector.” Jusuf Trbic told me that there

is no possibility of change from grassroots activism. Slavko Klisura

shouted, “Nema pokreta!” (there is no movement).

I don’t agree that there is no movement. All three of the sections of

the grassroots that I mentioned above are still working. However, the

system of corruption is too entrenched, and the movement is too weak,

for the grassroots to do it alone. And it happens that organizations

that once took risks have gotten grants, moved into comfortable

positions, and lost their bite. Other risk-takers will have to appear

and take their place. The effort ebbs and flows.

Here is something of what others are saying about change in Bosnia. I

have had the opportunity to meet with various people here who are either

working with agencies of the international community or are in positions

to provide intelligent analysis. Because most of what they say is “not

for attribution,” I will call them Warren, Bill, Barry, and Merima.

Republika Srpska Prime Minister Dodik is one of the most common topics.

People ask, “What will Dodik do?” and, “Is he really that

crazy/stupid/crude/nationalist?” Much of what Dodik does is seen as

pre-election performance designed to frighten people and gather votes

for his team. This evaluation applies to his threat to call for a

referendum on secession in the RS. Whatever else he is, Dodik is a

skilful manipulator and probably the most powerful politician in

Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Barry told me, “Dodik is so used to getting his way that his sense of

the other side’s breaking point may not be well calibrated… Dodik does

not want war, but he may get one if he pushes too hard for secession.

The question is how together the other side is.”

Like many other analysts, Barry said that Dodik is “a product of the

system” -- “We created incentives for Dodik to be what he is. He is the

beneficiary; he figured out that he could keep what the SDS (former

leading Serb nationalist party) gained, without their historical

baggage.”

As to the possibility for constructive measures coming from the

international community, Barry said, “We need to create conditions where

people will be able to make compromises. Now, that is still possible,

but it could become impossible. Political stagnation is bad, but

collapse would be worse. With Dodik leading, he could go too far. He

keeps pushing the red line further. And we are consistently lowering the

dike while the waves are getting higher.”

Barry, though not an employee of the international community, still uses

“we” in reference to the internationals. But he declares, “There is no

international strategy. There needs to be an arrangement that all three

sides can buy into, and feel protected. Then the country can function.

Dayton is not that arrangement.”

Putting it differently, Slavko Klisura earlier told me, “We don’t have a

constitution, we just have the Dayton document. That constitution is

fascist. It recognizes ethnicities, not citizens.”

Warren, closer to the international community, told me, “Don’t expect

pressure from the international community. The real pressure has to come

from the voters.”

Warren and Bill both spoke of the earlier years of the international

governance of Bosnia, under High Representatives Petritsch and then

Ashdown, as being more orderly times. Warren said, “We imposed a

constitutional structure. Under Petritsch and Ashdown the Dayton Peace

Agreement was stretched to its limits.”

When I asked Bill about the strategy of the international community, he

answered, “There is no strategy. Ashdown’s strategy was transition (to

domestic governance). This failed after 2006 because his reforms failed.

Since then there has been inertia. And the ambassadors, who are here for

three years, have no institutional memory…the biggest failure was of the

Ashdown period, and, of course, the immediate postwar period. Ashdown

saw the system as something to override, and he overrode it, but didn’t

change it.”

In frustration, Bill said, “Mother Teresa would become an extremist in

the present system.”

I spoke to Merima, another analyst. She outlined her hopes for the

future of Bosnia: “We are on the road to integration. Security is

important to Europe. There is already a Bosnia office in the new NATO

building in Brussels. So we are going into NATO. And if we are going

into NATO, then we are going into Europe.

Merima’s construction is logical. I hope that her understanding of

international dynamics proves to be accurate.

View of Sarajevo from Radoncic’s Twist Tower

POLITICS

The World Soccer Championship is

running all month in South Africa -- and in the kafanas of Sarajevo. You

can’t walk down the street without tripping over a wide screen. People

come out for the evening to drink a few beers and watch the games. I

admire the skill of the soccer players, wondering how someone can catch

a ball flying fifty meters through the air with his head, and then

deflect the ball off to just the right player another ten meters away.

At a certain point, talking to Slavko, it struck me that conversation

about the upcoming fall national elections, and about all the parties

and all the players, is a superficial thing. A distraction from real

life -- like talking about sports. Discussion of electoral politics, in

a situation where so little can change as the result of an election, is

stuck in the virtual realm. So much that matters to people here resides

in that realm. Is not religion a virtual thing, something you decide in

your head? And then if you use that abstract concept as a reason to vote

for someone, is that not absurd

Many politicians talk about that most abstract of things, the “national

interest” of their constituency -- as if Serbs, Croats, and Bosniaks do

not all in equal measure need health care, jobs, better pensions, and

security.

So religion and politics -- especially when mixed together -- become a

distraction. When someone asks you what religion you are, too often they

really mean, “Are you a member of my club?”

In response to my comment about politics being a distraction, Barry

agreed but said, “Talking about politics matters in that it defines the

realm of the possible.”

Meanwhile, of course, there are people who cultivate their identity, in

the face of such massive social trauma, and hold onto it “like a

drunkard to a fence,” as they say here (“drzi se toga kao pijan plota”).

You can’t deny the validity of someone’s moral lifeline. So the virtual

becomes more important than the concrete. But all this gets out of

control in the hands of skilful political manipulators.

It is easy to get tangled up when navigating in the virtual realm.

People talk about another ethnicity as if they are 19th-century

anthropologists. Marko (a Serb) in Foca told me, “The Muslims have this

pleasant custom of sitting and drinking coffee…” -- while we were

sitting and drinking coffee. Jure, a Croat in central Bosnia, told me,

“The Muslims are not industrious, they are content if they have a

comfortable place to sit and drink coffee.”

This kind of facile, essentially ethnic-chauvinist characterization

became fashionable in the 1990s, and it has been part of the process of

the creation of new identities in opposition to the “other.” It is

easier for people to think in this way now, as they are more physically

separated than they ever were before. The separation was the objective

of the war, and it succeeded to a huge extent.

I know many people who swear that they are anti-nationalist and that

they hold no prejudices. But genuinely arriving at that position takes

more work than most people are prepared to do. So I regularly find,

among the most agreeable and even delightful people, that some backwards

attitude reveals itself. It seems that the hardest thing to do is to be

completely consistent.

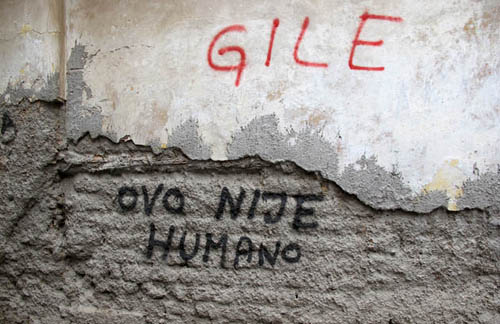

Graffiti in Vratnik:

“This is not human.”

*

I took a couple of walks in the Sarajevo hills with Sarah from Portugal.

Sarah pointed out to me that before the disintegration of Yugoslavia, it

was a more developed country than Portugal. Portugal has a population of

around ten million. Sarah told me that they are overcoming the problem

of slums there. I said, “There are probably over ten million people

living in slums in my country.”

Sarah is a remarkably bright and creative scholar, here to investigate

“genocide and collective memory” (my approximate description). We have

talked about how not only journalists, but scholars and others come to

this country for “a good story.” The observers are caught up in the

“story,” and the survivors and inhabitants of this country are caught up

in it too. It is unavoidable -- but must be treated with sensitivity.

Sarah talks about “genocide tourism” as an example of the worst of this

phenomenon.

Dusk view from a hillside neighborhood in Sarajevo

For more from Sarah, see

cafeturco.wordpress.com

TRAVNIK

As I was starting out on a trip

to Herzegovina, I visited some of my pal Steve Horn’s friends in Travnik,

in central Bosnia. Steve went to Bosnia (and vicinity) in 1970 with a

camera, and then came back thirty-three years later with his old photos

and another camera. He made a very fine book about the experience -- see

http://www.pictureswithoutborders.com/ .

Old Ottoman fortress in Travnik

I walked up to the fortress above the town for a beautiful view of

Travnik, nestled among the hills, with the river Lasva running through

it, fed by the tributaries Plava and Hendek. Travnik is surrounded by

those tight, dark fir and pine mountains that epitomize central Bosnia.

If you are not from a mountainous area, those hills can be mysterious

and foreboding. If you are from a mountainous region, Travnik feels like

a cozy, protected place. It was the capital of Ottoman-occupied Bosnia

for 150 years, and the home of Ivo Andric, Bosnia’s Nobel Prize winner

for literature.

I met Saban, who took me up in the hills to his cottage. He showed me

the pigeons that he raises as a hobby. He has over a hundred pigeons. I

asked if he earned anything from them, and he said, “No, they are just a

hobby and a loss.” Saban also has one peacock. I looked through the wire

mesh at it. His head was a little above my eye level, and his tail

feathers reached to the ground. He moved towards me and looked me in the

eye, and then let out a loud, “Piaao!”

Saban told me that peacocks have a better sense of smell than dogs, and

that in some places they are used to guard jails.

I met Steve’s friend Alen and Alen’s friend Erna. They play in a rock

band. They told me that they write love songs, and that most of their

songs are in English. I asked if there were any bands around that write

protest songs. They mentioned Dubioza Kolektiva. Erna said that “anyone

who does anything other than turbo-folk, if they’re introducing new

elements or writing in English, those are protest songs.”

Turbo-folk is a crude kind of modern, pseudo-folk music with a strong

Serbian influence, popular in kafanas all around the former Yugoslavia.

The lyrics range from banal to brutal.

In the evening I visited a local Croat family. Travnik used to be a

mixed Bosniak-Croat town, but since the war it has been dominated by

Bosniaks. Most Croats left during or after the war, but the family of

“Vilko” stayed. Vilko told me, “During the war, you prayed to God that

no one would call your (obviously Croat) name in the streets.”

Vilko said that his family was not able to leave the town in any case,

though many Croats left from the surrounding villages, and that those

villages are now all but empty.

Like everyone else in town, Vilko’s family was terrorized by Serb

shelling. By the end of the war there was no unscathed glass in their

apartment, not even in the interior doors. But the family also suffered

from intimidation and discrimination -- during the war and to this day

-- on account of being Croats. The family told me that the Bosniaks who

dominate Travnik do not hire Croats, regardless of qualification.

Hearing all this, I felt like I was amidst an embattled group of people.

Center of Travnik

The morning that I went to Travnik, right up the road in Bugojno there

was a terrible bomb attack on the police station. A member of a militant

Islamic group planted a land mine there, which did much damage

throughout the building and in the neighborhood as well. Neighbors said

it was stronger than anything they had felt during the war. One

policeman was killed, and several others were injured. The dominant

theory about the bombing attack was that it was a reprisal by local

Muslim extremists for local court proceedings against fellow extremists.

At the same time the religious (Muslim) observances were taking place

not far away at Ajvatovica. There, according to folklore, five hundred

years ago a religious mystic prayed for water. The mountains split and a

creek flowed through the gap, bearing water to the thirsty land.

The head Imam of the Islamic community, the Reis Ceric, gave a talk at

the massive gathering at Ajvatovica, stating that “Muslims are not

protected by the state of Bosnia-Herzegovina.” This statement was given

headline space by the popular but manipulative daily Avaz, published by

Fahrudin Radoncic, who recently founded his own political party. With or

without Ceric’s blessing, Radoncic apparently finds it useful to quote

Ceric in the promotion of his own political goals. The electoral

campaign is in full swing.