In this time of war, no commercial

airplanes fly into Ukraine. So toward the end of September, I

entered the country from Krakow, Poland by way of a long bus

ride. Crossing the border into Ukraine was slow, but without

complications. The rural area between there and Lviv was green

and idyllic, with a feeling of remoteness from civilization. I

saw a horse-drawn wagon, a sign advertising the New York Balkan

jazz group "PECTOPAH," and a billboard promoting the notorious

Azov regiment. Lviv was a contrast, with the atmosphere of any

other historic Eastern European city.

Having visited Lviv a few years earlier,

I spent a few hours reacquainting myself with the town. I

visited my favorite used-book flea market off Pidvalna Street,

and walked along Prospekt Svobody past the monument to Taras

Shevchenko, the prominent artist and poet who was instrumental

in spurring Ukrainian cultural pride in the 19th century. In the

courtyard by the Greek Catholic Church stood a panel exhibit

devoted to the history of the Holocaust as it had played out in

Lviv. One panel read, "We Remember," in large captions. Most of

the Jewish population of 110,000—almost a third of Lviv's

inhabitants—perished during World War II. The Lviv wartime

ghetto was one of the largest in all Europe.

I caught up with friends I had met a few

years earlier, and other people I met via social media. As I was

walking in the old section with my friend Artem, we saw a man

across the street, yelling to an imagined crowd. No one paid

attention to him. Artem explained that he was citing the Bible

and blaming "the Jews" for Ukraine's troubles.

I had visited Ukraine with my brother in

2019, not long after Volodymyr Zelensky was elected President.

Among other things, we traveled to Zaliztsi, a couple of hours

east of Lviv. Our grandmother had grown up there and emigrated

to the United States before World War I. That western part of

Ukraine, Galicia, had been ruled by the Austro-Hungarian Empire

since the late 18th century. Fifty years after her arrival in

the US, my grandmother still said that she had come from

Austria.

I tried to imagine my grandmother as a

girl, playing in that town when it was a Jewish shtetl. But

there was next to nothing recalling the rich Jewish life of

Zaliztsi, save a severely desecrated cemetery and a charmless

brick house commemorating some local sages of yore, built by

Israeli donors. I was glad that my grandmother escaped all this

history. Even before the Holocaust, there was extreme cruelty

perpetrated against the Jewish population during World War I,

just a few years after my grandmother left.

Remains of Jewish cemetery in Zaliztsi

In the course of visits to several

Ukrainian cities this year, I saw monuments to one war after

another, going all the way back to the Cossack rebellions of the

17th century. I pondered what it must be like for a person

growing up in Ukraine to be confronted every day with this

testimony to recurring violence in one's homeland. The trauma

associated with these events continues, obviously, to this day.

One friend, still distressed after the bombing of Lviv that took

place early in Russia's spring 2022 escalation, is reluctant to

venture more than a few blocks from home.

During visits with friends, I regularly

encountered expressions of patriotism and fervor for the defense

of Ukraine against the Russian assault. I heard of a musician, a

woman whose talent was so valued that she was offered a

sponsorship to immigrate to the United States. Instead, she

joined the army and went to the front. My friend Oksana told me

how her husband, over 50 years old, had been mobilized into the

defense. He was old enough to have served in the Soviet army.

Oksana laughed wryly as she noted that due to this background,

her husband was required to take an oath of loyalty to the

Ukrainian army.

Oksana commented, “I feel so sorry that

the blossom of our nation is away fighting and being killed; I

don’t have the words to express my gratitude to the boys and

girls who are out there protecting me.” When I brought up the

proposal of negotiations with the Russians, regularly suggested

by people who are distant from the war. Oksana countered,

“Negotiations with whom? With a crocodile?”

In early October there was the Jewish

harvest celebration of Sukkes, and I went to the Jewish

community center for an observance of the holiday. Other

visitors were present from abroad; there was food, song, and a

good bit of talk by the rabbi, who wore a camouflage yarmulke.

I found it disconcerting that the Jewish

community center was located on Stepan Bandera Street. Stepan

Bandera was a Ukrainian nationalist who collaborated with the

Nazis during the early part of World War II. He was one of the

leaders of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, which

fought on the side of the Germans in Ukraine shortly after the

invasion of June 1941. Extreme Ukrainian nationalist members of

the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (OUN) carried out pogroms against

Galician Jews, and massacred Poles in great numbers as well.

Bandera's hope for an independent Ukraine did not last long, as

the Nazis soon arrested and jailed him.

As the Nazis were losing the war in

1944, they released Bandera so that he could help lead a

continued resistance to the Soviet regime that had taken over

the western part of Ukraine. Bandera remained in Germany, and

the resistance was suppressed in the second half of the 1940s.

The KGB assassinated him in 1959. In 2009 a postage stamp bore

Bandera's portrait, and the next year, then-President Yushchenko

proclaimed Bandera a national hero; this measure was marked by

protests in some parts of the country.[1]

A cult of Bandera has carried on

episodically, with more success in some parts of Ukraine than in

others. I noticed a lone red and black flag, the standard of the

OUN, planted near the center of my grandmother's city of

Zaliztsi; today it can be seen in other parts of eastern Galicia

as well. Counter to this reminiscence, in the post-Maidan period

author Marci Shore quoted respondents as saying that "A lot of

people in my [younger] generation don’t know who Bandera is."[2]

Kyiv: grim monuments

I traveled to Kyiv, the capital of

Ukraine. Again, I spent some time re-familiarizing myself with

the city and catching up with friends and new acquaintances. The

grand cathedrals within walking distance of each other in the

upper city, the St. Sophia Cathedral, St. Andrew's Church, and

St. Michael's golden-domed monastery, still shone with their

ancient glory.

The courtyard in front of St. Michael's

contained a striking display of captured Russian military

vehicles including rusted tanks, armored personnel carriers, and

trucks. Visitors had inscribed graffiti on the relics,

commemorating places of resistance and destruction: Bucha, the

Kakhovka dam, Mariupol, Bakhmut, and more. Someone wrote "F**k

Putin,"—a sentiment expressed in many forms in the souvenir

shops of Ukraine.

Display of captured Russian war

vehicles in front of St. Michael's Monastery

In a panel display, there was a series

of photos comparing the destruction in various towns of Ukraine

to that of the Warsaw Ghetto. Inscriptions were in Polish,

Ukrainian, English, and German. Details of rubble in the two

locations, more than 75 years apart, were not easy to

distinguish.

I looked around for the prominent statue

of Bohdan Khmelnytsky, which I remembered viewing in the square

by St. Sophia Cathedral, until I

realized that it had been concealed from view by sections of

plywood set up to shield it.

Since Khmelnytsky is such an important

figure in Ukraine's foundational historiography, a bit of

background is important here. He was the leader of the most

successful Cossack rebellion against Polish domination over

Ukrainian lands under the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The

rebellion, culminating a succession of Cossack uprisings over

the previous century or more, began in 1648. For a time the

Cossacks, first in cooperation with the Crimean Khanate, and

then in an enduring alliance with an ascendant Moscow, carved

out a relatively independent "hetmanate."

This episode on the verge of the modern

era heralded an early upwelling of Ukrainian national sentiment,

particularly as viewed by later historians. Present-day

Ukrainian patriots look back to Khmelnytsky as the closest thing

to a founder of modern Ukraine. However, there were tragic

elements of his movement and its outcome. One was that,

desperate for military assistance to defeat Polish forces,

Khmelnytsky made a fateful pact with Moscow. By the late 1650s

Moscow had conquered Kyiv and much of the eastern part of

Ukraine. At this point, it arranged a détente with Poland, and

the nascent Cossack state was no more.

Another negative aspect of Khmelnytsky's

rebellion was a series of catastrophic massacres of a large

portion of the Jewish population of Ukraine. History-minded Jews

remember these atrocities much more than do Ukrainian patriots.

Estimates of the number of Jews killed range from a very

conservative 20,000[3]

to well over 100,000, with several hundred Jewish settlements

destroyed. This period left the Jewish community of Ukraine

decimated. Among Jews who remember this history, today the

mention of Khmelnytsky, and the Cossacks in general, evokes not

Ukrainian patriotism, but dread.

With the abundance of places named after

Khmelnytsky and Bandera on my mind, I happened to speak with a

Jewish-American friend who is exquisitely conscious of history,

both Jewish and Ukrainian. He said, "The Ukrainians need better

heroes."

Every city I have visited hosts a street

named after Khmelnytsky, and indeed an important city in

Podolia, near Khmelnytsky's base of operations, bears his name.

And in Kyiv, the no-star "Hotel Minimum" where I slept was

conveniently located on Bohdan Khmelnytsky Street.

Banner honoring Mariupol resistance

Behind the boarded-up monument of

Khmelnytsky near St. Sophia Cathedral was a massive banner,

easily fifteen meters long and ten meters high, covering up most

of the side of an apartment building, paying homage to the

devastated city of Mariupol. During the ten-odd days that I

spent in the city, I did not hear an air-raid siren as I had in

three other cities I visited, but there had been sporadic

Russian attacks, and there were to be more.

Back toward the center of the city, the

vast Maidan Square still bore mementos to the "Revolution of

Dignity" that took place there in late 2013 and early 2014. Now,

a new layer of commemorative articles has been added. In one

prominent space there are thousands of small Ukrainian flags

planted in the ground, each one commemorating a soldier fallen

defending the country.

Memorial flags at Maidan Square

In that early part of October, bad news

was coming to Ukraine from a couple of directions. In elections

in neighboring Slovakia, the right-wing populist Robert Fico won

the position of prime minister. He promises to be an ally to

Hungary's autocrat Viktor Orban, who has used his veto power in

the European Union to prevent that body from granting aid to

Ukraine.

At about the same time, in the United

States the Republican-engineered "emergency" budget that

arranged for the continuation of funding for the US federal

government removed $6 billion in assistance for Ukraine defense.

This was just one early move in a series of Republican measures

that will carry on into 2024, holding the US back from supplying

desperately needed military aid to Ukraine.

Working in Hostomel

One day, I joined up with volunteers

from a loose network called "Brave to Rebuild" and traveled to

the nearby town of Hostomel. About fifteen of us, both

Ukrainians and foreigners hailing from Germany, Sweden, Canada,

and many places in between, spent the day removing rubble and

earth from the foundation of a house that had been bombed by

Russian forces in May of 2022.

Hostomel is the northernmost of three

adjacent cities, together with the notorious Bucha and Irpin.

Russian forces attacked all three in late February of 2022, at

the beginning of their full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Bucha

took the brunt of the atrocities, with over 450 civilians raped,

tortured, and killed.

One of the targets of the Russians was

the international cargo airport in Hostomel. They tried to land

at the airport, but Ukrainian forces shot down some of their

helicopters, and bombed the runway so that the Russians could

not use it. This helped to foil the Russians' plan to take over

Kyiv.

The Russians held the three towns for

about two months before being repelled by Ukrainian forces.

Anton, the owner of the house whose foundation we worked to

excavate, told us that Russian forces had occupied his home for

three days. He said that he drank with his uninvited "guests,"

but they also beat him. "It was terrible," Anton said. But he

laughed as he recounted that the soldiers told him, "We will

take Kyiv in three days."

When the Russian troops were driven out

of the area, Irpin was mostly devastated; Hostomel, less so. But

the Russian forces took up position behind the towns and

continued to shell them for the next couple of months. That is

when Anton's house and some other buildings nearby were

destroyed.

|

|

|

War

destruction in Hostomel |

Traumatic history with the Russians

The reasons Ukrainians wish to remain

independent from Russia are obvious, as are the reasons for

their resentment of their bigger neighbor. They go much further

back in history than the rape of Bucha in February of 2022. One

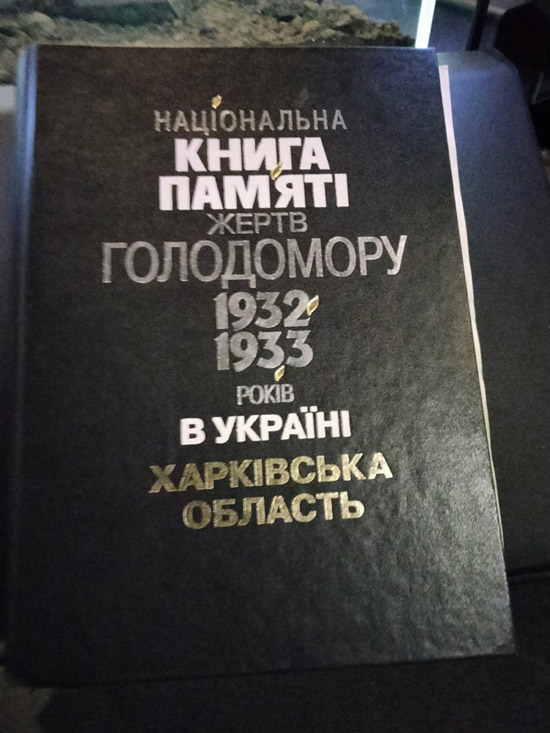

event that stands out in that history is the Holodomor, the mass

death by starvation that took place in 1932 and 1933, but had

precursors going back to the early consolidation of Soviet

power. On a free day, I visited the Holodomor Genocide Museum,

up the hill from one of the bridges over the Dnipro.

The museum was housed in one large,

circular room; it was semi-darkened, giving it a somber feeling.

You could walk in one direction around the room and examine a

series of stands pertaining to each oblast (region) of Ukraine.

Each stand held a thick book with the compiled names of those

who starved. One book that I looked at was a thousand pages

long, each page bearing many names of the victims. Displays

around the perimeter of the room described how the Soviet regime

engineered this starvation.

Ukraine is widely known as possessing

one of the richest agricultural lands in Europe, supplying much

of the world with grain. While Lenin had made a gesture to

Ukraine's national identity, his regime took immediate measures

to exploit its agriculture and incorporate it into the Soviet

economy. One display at the Holodomor museum shows a May 1921

telegram from Lenin to military officials reading, "Now the

question for all Soviet power: The matter of life or death for

us is to collect 3-5 million tons [of grain] in Ukraine. We need

to take everything, surround with a triple cordon all the places

of extraction, do not miss a pound, do not allow them to loot.

Let's put things in a military fashion."

Later in the decade under Stalin, and

into the 1930s, pressure on Ukrainian peasants was increased in

the extreme. Stalin enforced collectivization that was

demonstratively counterproductive and targeted peasants, who

resented this move. With the Soviet regime requisitioning

produce and directing it away from the rural areas to the cities

and to Russia, peasants began starving.

Timothy Snyder's book Bloodlands:

Europe Between Hitler and Stalin recounts the Soviet

regime's measures in a detailed, blood-chilling manner. The army

targeted intellectuals and community leaders. A woman was shot

for "stealing" an ear of corn from her own field. People

practiced cannibalism within their own families. In the course

of less than two years, at least 3.5 million people starved. One

sometimes hears figures that are much higher, which could

include starvation regimes that were underway in other parts of

the USSR.

|

|

| Museum of the Holodomor

Genocide |

Book

of Holodomor victims |

Visiting the scene of another grim

episode in Ukrainian history, I went to the site of Babyn Yar

(Ukrainian—"Babi Yar" in Russian), where the largest Nazi

massacre of World War II took place. The site is within the city

of Kyiv, at the end of the Metro route to Syrets. It is a vast

space, now converted into a memorial park, containing the ravine

where thousands of people were killed and buried. In September

of 1941, Nazi troops massacred nearly 34,000 Jews there. In the

course of the ongoing German occupation of Kyiv, ultimately

between 100,000 and 150,000 Jews, Roma, and Soviet prisoners of

war were killed at this place. The killings went on until late 1943, when Soviet troops

retook Kyiv.

One side of the memorial park is

forested with hardwood trees; in the center of it is a

depression, the ravine where people were killed. There is an

imposing Soviet-built monument in the middle of it on a rise in

the land, dedicated to the "Soviet citizens" who were massacred.

This phrase reflects standard Soviet historiography. While Jews,

Roma, and other Ukrainians suffered the most during World War

II, in the dominant version these groups were elided into

"Soviets."

Soviet statue

This falsification of history of the

massacres at Babyn Yar was not addressed until Ukrainian

independence in the early 1990s. It was in that decade that most

of the monuments now seen at Babyn Yar were installed or

re-interpreted. The park was developed into a much richer

memorial, not only to the Jews who were killed, but also to the

victims among the Roma, Ukrainian intellectuals, and Christian

clergy.

In early March of 2022, soon after the

start of Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russian planes

bombed a radio tower near the park. They also bombed the

building of the Babyn Yar museum, within the park.

As I was walking, it rained a drizzle. I

remembered what Fata, my landlady in Sarajevo, once said when it

rained on the anniversary of the Srebrenica genocide: "When it

rains, it means that God is angry." I wondered why it only rains

some of the time.

Monument to children victims at Babyn Yar

I arrived at the monument to the

thousands of children killed at Babyn Yar. It was mid-October,

and I couldn't help but think about the hundreds of children

being killed right now in Gaza.

Talking about heroes

It may seem that I went to Ukraine for a

tour of grim monuments, but that is not the case. Rather, I felt

compelled to visit the country as a gesture of solidarity with a

nation that I believed (and still believe) was under a brutal

and unjustified assault from its bigger neighbor. I believed

that Ukraine has a right to defend its sovereignty on the whole

of its land, and that powerful states abroad should help in that

defense—arguably for their own self-interest. I wanted to learn

enough to be better able to approach a variety of questions

posed by those, especially on the Left, who do not share those

beliefs.

I tried to arrange conversations or

interviews with as many people as I could. In addition to

friends and further connections, I had appointments to interview

people working at Karazin University in Kharkiv (see journal

#1). In Kyiv I had the opportunity to meet with two young women

who worked in local corporate offices. I met with Sofia and Anna

at the Honey Café, in the historic center of the city. In this

noisy coffee house we were able to have a wide-ranging

conversation.

I started out by asking the two women

how they viewed the Maidan Revolution that had erupted in

2013-2014, beginning in their own city: "Was that something that

you and your friends were enthusiastic about?" Anna responded,

"We were very young then, but when we see what happened, it had

to do with wanting to be part of the West."

I asked, "What does it mean to you, to

be part of the West?" Anna said, "First of all, having visas to

go to Europe. Before, it was very expensive, and it was very

hard to get visas. The wish of Ukrainians to go to Europe—not

only physically, but culturally and economically, was strong. We

don't want to live the same life as the Russians. We want to

have good jobs, a good level of cultural development of our own.

And Yanukovych, essentially, was saying no to our wishes. It was

obvious that he just wanted to stay on the Russian side."

Viktor Yanukovych was the profiteering

prime minister of Ukraine between 2010 and 2014, when he was

forced by the Maidan protests around the country to flee to

Russia. The protests were in response to his failure, under

pressure from Russia, to sign an association agreement with the

EU. Bitterly disappointed citizens of all ages, classes, and

political persuasions filled the Maidan Square through several

months of freezing weather. In February 2104, the regime's

special police shot around one hundred protestors. This only

intensified the anger of the citizens, and Yanukovych was soon

forced out of office.

Sofia expressed resentment of Russian

designs, saying, "It is as if they, the Russians, consider us to

be like some tribe, that we are not a people. They would like

this all to be Russia, with no border, but we would like to

preserve our independence and our identity. The Russians, they

are more an Asian people than Slavic.

"Before Maidan, when Russian people came

to Kyiv it was always okay. If you spoke Russian, it was ok. We

were speaking Russian until February 2022. In my family, it was

generally our language, because my parents were Soviet people.

And Russians say that Ukrainian is just a dialect of the Russian

language. People were pressured not to use Ukrainian, until

after we got our independence. So many schools, many

universities, held classes in Russian, and many TV shows were in

Russian. Whole generations were raised with this. But now we are

working to be proud of ourselves as people who feel like

Ukrainians. It has been a short time, but the process is now

going faster. We decided to avoid Russian in all areas, for

people who know the Ukrainian language."

Anna added, "About 15 years ago our

government, when Yushchenko was prime minister, decided on a

policy of Ukrainianization. So TV shows started being broadcast

in Ukrainian, and most of the songs on the radio are in

Ukrainian."

Anna spoke about the Russian invasion,

which started in 2014 after the Maidan Revolution. At that time,

Russia quickly moved into an unprepared country and took over

parts of Donbas in the southeast, and the entire Crimean

peninsula.

Not all Ukrainians objected to Russia's

assault at that time. "There was nostalgia among some of the

older people for the Soviet period, because they associated that

time with stability over an uncertain future," Anna said. "But

at the same time, a huge majority of Ukrainians had a strong

historical memory and a sense of grievance against Russia. We

remember Stalin and the genocide of the Holodomor. And we

remember that Ukraine was not always under the domination of

Moscow. This war started 400 years ago; now there is a terrible

escalation, but we hope this will be the last of it."

I asked what happened 400 years ago.

Anna said, "At that time, Poland and Lithuania were one kingdom.

And there was a revolt against Poland and Lithuania by one of

the Cossack warriors, the hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky. He fought

against Poland for the independence of Ukrainian land. When he

saw that the army of Cossacks was not enough to defeat Poland,

he decided to ask Moscow for military help. At that time, Moscow

was not a big power."

I asked, "Was that a mistake?" Sofia

answered, "Oh yes, it was a very big mistake, because in that

way, he gave power over Ukraine to Moscow."

That was in the mid-1600s, and by a

couple of generations later, Moscow had become the center of an

empire with domination over the traditional Ukrainian lands.

This domination was compounded over the centuries. For example,

many Russians were moved into depopulated parts of Ukraine,

especially in the southeast, after the Holodomor.

Sofia and Anna lamented the destruction

accompanying Russia's full-scale invasion of 2022. Sofia

recalled, "At the beginning, Kyiv was empty. Shops were closed,

and many of our friends left. We both stayed here, because we

wanted to help in the defense of our country. And we didn't know

what was happening. We only found out about things like Bucha

much later, in April. We knew that the occupation army was

there, but we didn't even imagine what they were doing.

"They are killing people in places like

Izum, and in the Kharkiv region; and it was terrible to see what

happened in Mariupol, with just insane numbers of civilians

killed. And they are taking Ukrainian soldiers and beating and

killing them. It is genocide."

I noted, "Genocide is a UN Convention;

it means something specific. It means to harm intentionally, in

whole or in part, an ethnic, religious, or racial group by

causing physical or mental injury or, among other things, by

taking the children away."

Anna: "You see how many children were

taken away and given to Russian families."

"Now," she said, " I would like to go to

the front, but I can't. But I can stay and help here."

"We see that the US is wavering on the

subject of military aid to Ukraine. Are there many people in the

USA who support Trump, and say you shouldn’t help Ukraine? It is

a very dangerous situation, with Russia getting weapons from

China and other countries. So to protect ourselves, we need to

have our own weapons manufacturers, our own weapon supply.

Because we can't just keep asking every country for help and

money. We will have to have more of an arms industry."

I commented that there are people in the

West who advocate early negotiations between Ukraine and Russia,

and that the US should stop sending weapons to Ukraine. Sofia

asked, "What will you negotiate?" I admitted that I had not

heard any concrete suggestions. Sofia responded, "Unfortunately,

that is not a solution, because 'negotiation' just sounds like

leaving the situation as it is, changing the map of Ukraine.

There should be no changes like that."

Sofia and Anna had heard that there were

large numbers of Russians entering Poland and other parts of the

European Union, without obstacles to their immigration. Anna

said, "It is not acceptable to allow Russians to move to other

societies. They come to another country, and they aren't able to

learn a new language, and they aren't able to make use of being

there. Meanwhile, Ukrainians are having difficulty emigrating to

the US."

I pointed out that many of these

Russians in exile are people who don't agree with Putin.

Sofia: "Why don't they do something to

remove his power, or his money? It's a country of 140 million

people, but they are afraid. What should I do? They are afraid,

but we are dying because of them. It's their problem."

I answered, "There are people who tried

to protest, and now they are in jail for 15 years, for as little

as a comment on social media."

Sofia: "It is their country. They have

to do something. We took care of Yanukovych; we organized and

forced him to leave."

I responded, "Slava Ukraini," and moved

on to another question.

Monument to Mother Ukraine above Dnipro River

I asked, "I'm wondering who would you

and your friends say your heroes are, now, or in history?"

"Now," Sofia said, "my heroes are the

soldiers on the front, and the people who stayed here in Kyiv,

and didn't leave. They stayed here to help."

Anna added, "Another hero I would

mention, from the past, is Stepan Bandera, who fought more than

70 years ago, fighting the Russians. But a Russian agent killed

him. The KGB, they killed him in Germany."

"So he’s a hero?" I asked.

Anna, "Yes, he’s one hundred percent a hero. The identity of the

Ukrainian people is related to his history. He promoted the idea

of an independent Ukraine. He was ready to die for an idea, for

Ukraine."

I said, "I have heard of this, but also

that he collaborated with the Germans."

Anna said, "It was just in the start of

World War II, because they had no information about what the

German army was going to do in the war, but they were ready to

collaborate with anybody against the Russians. They knew what

the Russians would likely do to us, but they didn’t know what

the Germans were going to do. The Red Army was much more

aggressive here. My grandparents said they expected that if the

German army came to Ukraine, they weren't going to kill people.

It was just, 'Okay, they occupied here.' Most of Ukraine hated

the Soviet government; they hated the things they had done here

in the last ten years before the war. There was not much choice.

You could go with the Red Army, or you could go with the German

army."

As I ponder these words, trying to

receive them without judgment, I remember that most of America's

currency and coinage glorifies slave owners and Indian killers.

It is the same with our streets named after Washington,

Jefferson, Jackson, not to mention Jefferson Davis and Robert E.

Lee, just now experiencing a bit of revision in the South. And

our heroes are not only symbolic; they are in our minds. We need

a Revolution of Dignity, and better heroes, here in the US as

much as anywhere.

I'm not sure if anyone consciously

chooses to be a hero. However, the look of it is that Ukraine is

getting thousands of new heroes today, perhaps better ones. I

fervently hope that their sacrifice is recognized and that it

will prove to be worthwhile.

[1] "A Fascist Hero in Democratic

Kiev," by Timothy Snyder, New York Review of Books,

February 24, 2010

[2] p. 47, The Ukrainian Night: An

Intimate History of Revolution, by Marci Shore (Yale

University Press, 2018).

[3] p.

99, The Gates of Europe: A History of Ukraine, by

Serhii Plokhy (Basic Books, 2021)